Ukraine a setback in China’s eastern Europe strategy

Just three months ago, China was in diplomatic overdrive to establish a grand plan for economic and political cooperation with central and eastern Europe (CEE) at a summit with 16 regional leaders in Bucharest.

Just three months ago, China was in diplomatic overdrive to establish a grand plan for economic and political cooperation with central and eastern Europe (CEE) at a summit with 16 regional leaders in Bucharest.

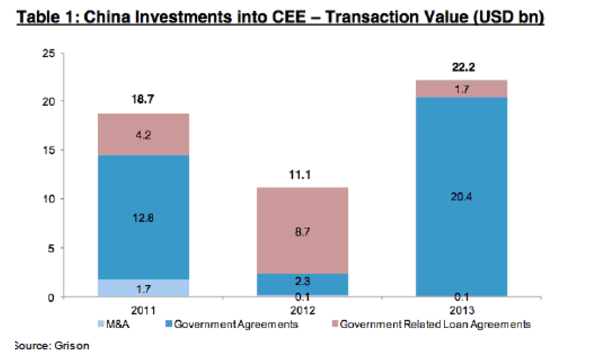

Since then, more than $19bn in Chinese investment and loan pledges have flowed to the region, outstripping in scale any previous phase of bilateral economic engagement, according to research by Grison’s Peak, a London-based merchant bank. The $19bn plus in pledges since November accounted for the lion’s share of a total of $22.2bn in signed loan and investment deals between China and the region for all of 2013, the Grison’s Peak figures show.

But “plans cannot keep pace with changes” as a Chinese phrase puts it. The revolution in Ukraine has thrown up a series of delicate questions for Beijing, which had a “strategic partnership” with the government of ousted president Viktor Yanukovich.

Ukraine was a key plank in Beijing’s CEE strategy. Of the estimated $19bn in investments and loans announced since November, $8bn was destined for Ukraine.

In addition, most of a further $10.9bn for Romania, $783m for Macedonia, $507m for Hungary and $306m for Serbia was in the form of Chinese investment and loan pledges, according to data collected by Grison’s Peak.

Ukraine has several key attributes from Beijing’s point of view. Logistically, it is a gateway to China’s big markets in western Europe as Beijing ramps up rail freight exports along the “iron silk road”. Its farmland, already the object of ambitious leasing schemes with China, could help secure Chinese imports of grain. Strong military ties include Kiev helping to build engines for Chinese fighter jets and cooperating

on other projects as part of the strategic partnership.

For these reasons and others, Beijing had extended about $10bn in loans to Ukraine even before the $8bn in Chinese investments promised at the end of last year. A key question now is how much of an impact the revolution may have on these commercial arrangements and on Beijing’s broader plans for engagement.

“I don’t see that this development is likely to change China’s investment policy very much,” said Rana Mitter, professor of history and politics of modern China at Oxford University. “It seems to me that China does not have the ideological commitment that Russia has to a particular view of Ukraine.”

“China’s major issue these days is to encourage other countries to serve its security and trade interests, not to pay much attention to the form of those governments per se,” Mitter added.

This type of pragmatic approach would be broadly consistent with Beijing’s nuanced diplomatic stance during the protests against Yanukovich’s government. The foreign ministry hedged its bets, supporting Kiev’s efforts to “preserve stability” but expressing respect for the “people’s choice”.

China’s main preoccupation now will be protecting its economic interests in Ukraine, said Bill Bishop, author of the Sinocism China Newsletter. But it will tread carefully so as to avoid antagonising Russia, which views Ukraine as within its sphere of influence. “I assume Beijing does not want to be at odds with Russia and [Russian president Vladimir] Putin over this, nor does it want a ‘victory’ for the west [US and EU] in a colour revolution,” Bishop said.

“Yes, Beijing will want to protect their economic interests but is there even a new government with whom they can negotiate?” he added. “Ukraine clearly needs cash and Beijing could play a role in a bailout, but I doubt they would do that given the uncertainty and Russia’s concerns.”

The deals struck during Yanukovich’s visit to China in December were for investments in energy, infrastructure, ports, airlines and food. The largest was with Wang Jing, a Chinese entrepreneur, who signed a $3bn agreement for the first phase of a deep water port construction project in the Crimean peninsula.

The port would be designed to redistribute rail freight flows from the east to Europe by cutting 6,000km off the current shipping routes. A second phase in this envisaged project, costing $7bn, would be focused on grain elevators, crude oil reserves and natural gas production bases, according to Grison’s Peak.

However, with armed men seizing Crimea’s regional parliament and government buildings on Thursday amid fears that separatists could split the region from Ukraine, the outlook for Wang’s Crimean port investment looks bleaker.

Some doubt may also attend the closeness of the strategic ties that Kiev under Yanukovich had built up with Beijing, analysts said. Much in this regard depends not on Beijing but on the attitude of Ukraine’s new leaders.

Nevertheless, in other areas of its CEE strategy, China is showing no sign yet of scaling back the momentum. In one example this month, Viktor Orban, Hungary’s prime minister, met with Li Keqiang, his Chinese counterpart, and announced that they had agreed on the financing of a Budapest to Belgrade rail project which they had proposed at the China-CEE summit in Bucharest last November.

Orban appeared to be keen on seeing further Chinese investment in infrastructure in CEE countries. “Highways and high-speed railways in the North-South direction are still not completed… and central European countries lack resources. We believe we have cooperation opportunities with China in this respect,” Orban was quoted in China’s official media as saying in Beijing.

PRESS ARTICLES 2015

- 12 December 2015 China to aid indebted African sovereign

- 25 November 2015 China’s New Silk Road Dream

- 22 October 2015 – Chinese investment along One Belt One Road revealed

- 16 October 2015 – Why we should hold out a friendly hand to China

- 10 Sep 2015 – Bangladesh favours Japan for port and power plant, in blow to China

- China Takes Its Debt-Driven Growth Model Overseas, 6 August, 2015

- 1 July 2015 – Massive Chinese lending directed to Silk Road

- 15 June 2015 – Chinese overseas lending dominated by One Belt One Road strategy

- 31 May 2015 – Chinese policy banks perform better since launch of Belt and Road Initiative

- 31 May 2015 – Belt and Road Initiative – Xin Hua

PRESS ARTICLES 2014

- 30 September 2014 – The signs are that Balfour Beatty has not yet reached the bottom – The Independent – Ben Chu

- 26 to 28 September 2014 – Terra Parzival Michaelmas 2014 Council Meeting!

- 28 August 2014 Zhang Chunyan in London and Zheng Yangpeng in Beijing – China Daily Europe

- 16 July 2014 – Nationale Suisse

- 27 February 2014 – Ukraine a setback in China’s eastern Europe strategy – Financial Times – James Kynge

- 20 February 2014 – Could China’s credit hangover prove to be a headache for HSBC? – The Independent – Ben Chu