Banks have ramped up lending to Chinese companies for projects abroad

Wall Street Journal, 6 August, 2015 By ANJANI TRIVEDI

HONG KONG—As Beijing grapples with a sluggish economy, a heavy debt burden and sagging financial markets at home, it is pushing through a new wave of credit-fueled overseas investment to stir growth.

For years, Chinese banks lent heavily to the country’s big state-owned companies so they could invest in new infrastructure, fueling rapid growth. But that strategy has maxed out. Many industries are now suffering from overcapacity.

For years, Chinese banks lent heavily to the country’s big state-owned companies so they could invest in new infrastructure, fueling rapid growth. But that strategy has maxed out. Many industries are now suffering from overcapacity.

The solution: Export the debt-driven growth model.

In the past year, Chinese banks have ramped up lending to Chinese companies to head abroad and take part in infrastructure joint ventures. They have also lent more to a host of overseas borrowers, from shipping companies in Greece to renewable-energy projects in Malaysia, to fund the construction of dams, power plants and railroads.

The low-cost capital has usually come with a key condition: The projects must buy Chinese goods and employ Chinese workers.

Between January and June of this year, projects contracted by Chinese companies abroad generated $67.54 billion in revenue, up 9.7% from a year earlier, according to data from China’s Ministry of Commerce. At the same time, Chinese companies collectively signed $86.67 billion of new contracts, up 6.9% year over year. And as of June, the value of projects completed by Chinese companies, or in the works, totaled $1.45 trillion, according to the data.

The push to lend abroad can come with geopolitical benefits, helping China cement ties with allies such as Venezuela and countries in Central Asia. But it is also deepening China’s dependence on debt to fuel its economy.

In an official statement in late December last year, Beijing said it would ramp up financing for Chinese companies that are “going global,” noting it would help “make more use of excess production capacity.”

“In essence, what they are doing is lending money to build infrastructure, to increase GDP growth,” said Henry Tillman, chairman and chief executive officer of Grisons Peak LLP, a London-based advisory and investment-research firm.

With cheap funding available from so-called policy banks—government-controlled lenders such as China Development Bank and China’s Export-Import Bank—or large commercial banks, Chinese companies heading abroad are often well-placed to win big contracts. Last year, Export-Import Bank lent €687 million ($749 million) to the government of Montenegro to finance a portion of the 170-kilometer stretch of an expressway connecting the Eastern European nation to Serbia.

The 20-year loan, at a fixed interest rate of 2%, came a year after Montenegro had selected state-owned China Communications Construction Co. and its subsidiary, China Road & Bridge Corp., as the top bidders on the project, according to a government news release at the time.

The loans’ terms stipulated that just 30% of the work would have to be subcontracted to domestic companies. Of the roughly 4,000 workers that the project is expected to employ at its peak, just 354 Montenegro workers have been hired thus far, according to a local media report this past week.

Earlier this year, Indonesian state-run coal producer PT Tambang Batubara Bukit Asamtook a 45% stake in a newly created joint venture with China Huadian Corp. to build coal-fired power plants. About 75% of the project will be funded by a $1.2 billion loan from China’s Export-Import Bank.

Russia’s MegaFon signed its eighth deal with China Development Bank last December, taking on a $500 million, seven-year loan to finance the purchase of equipment from Huawei Technologies Co.

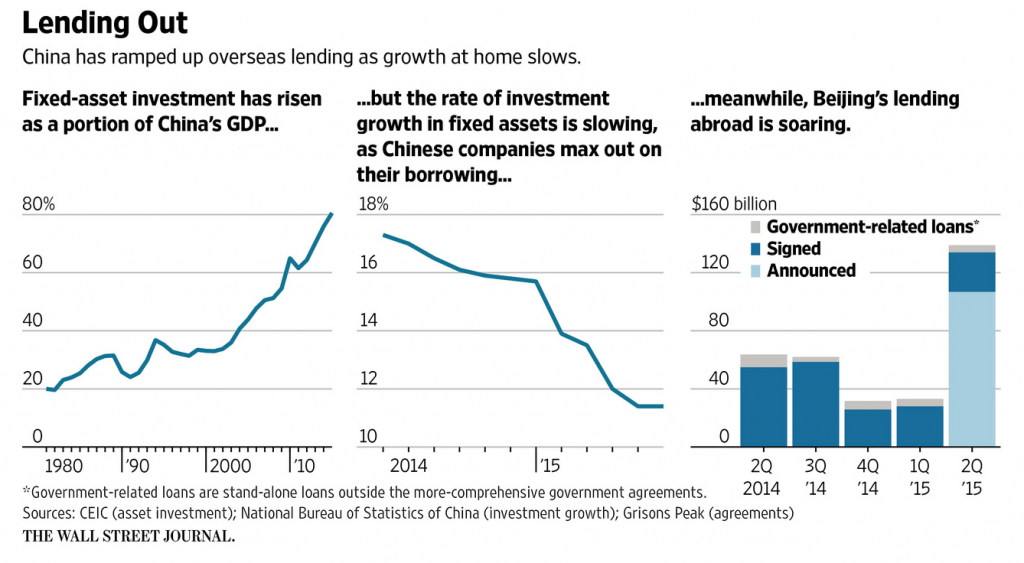

China has been lending to foreign borrowers for more than a decade, but this year’s push comes as its economy has been growing at its slowest rate since the financial crisis. Several rounds of stimulus, including interest-rate cuts, have failed to boost fixed-asset investment, in part because companies and local governments have reached their borrowing limits.

Economists estimate China now needs more than three times the amount of debt for every incremental yuan of GDP growth it needed a decade ago. China has increased its debt load from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion as of the middle of last year, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

Government agreements, such as for assistance to build infrastructure or trade financing, between the world’s second-largest economy and other countries, including India, Pakistan and Russia, increased by four times in the second quarter of this year, totaling $134 billion, according to data from Grisons Peak. Loans backed by the government, usually related to the agreements, totaled $19.6 billion in the quarter, with most of them involving projects directly linked to Chinese companies.

Overseas borrowers can often get loans from policy banks at lower rates than they would get elsewhere in international debt markets. Some of those getting loans would normally find it impossible to get funding in foreign markets, analysts say.

China’s push is also supporting large private companies. In May, China Development Bank and the Industrial & Commercial Bank of China together committed $3 billion to Indian telecommunications operator Bharti Airtel Ltd., two months after the company had signed a collaboration agreement with China Mobile Ltd. Bharti also has partnerships with Chinese telecommunication companies ZTE Corp. and Huawei Technologies.

International investments now make up almost one-fifth of China Development Bank’s loans, including an approximately $2.4 billion credit line to South Africa’s state-owned transportation company Transnet Ltd. to fund the manufacture of almost 600 locomotives with the state-run China Railway Rolling Stock Corp.

With China’s overseas lending increasing, the number of people working on contracted projects has also grown. In the first six months of the year, 264,000 Chinese workers traveled abroad, up by 9,000 from a year earlier, according to official data from the Ministry of Commerce, bringing the number of overseas workers to more than one million.

Still, China’s overseas lending has come with its share of snags. State-owned companies building dams in Malaysia have frequently been hit by local protests against displacement and environmental concerns, disrupting construction work. In Indonesia, Chinese state-owned companies that have built a series of power plants have come under fire over the quality of their construction.

China Three Gorges Dam Corp., the state-owned company behind the world’s largest dam and one of the world’s largest hydroelectricity companies, is typical of big Chinese companies getting support to expand abroad as its home markets slow. Last year, the company said it received government subsidies for international investments that are 10 times the level it received in 2012. Earlier this month, it issued its first offshore public bond, totaling $1.5 billion, to fund overseas investments and projects.

The company plans to invest 8.5 billion yuan outside China between this year and 2017, more than double what it spent overseas in the past three years. Meanwhile, its domestic capital spending is set to shrink by 14%.

But operating revenue from the company’s overseas investments has fallen over the past three years. In 2014, it effectively wrote off almost $100 million of investments in South Sudan and Pakistan. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Analysts warn that these undertakings could eventually weigh on China, if borrowers are unable to repay the loans. The Chinese government “will assume greater credit risk as it gradually diversifies some of its sizable foreign-reserve holdings into emerging-market foreign direct and portfolio investments,” analysts at Moody’s Investors Service noted in a recent report.

PRESS ARTICLES 2016

- 7 November 2016 China’s M&A deals in UK hit record in mid-2016

- 24 October 2016 Nearly $40bn in Chinese acquisitions pushed back by west Premium

- 13 October 2016 China rethinks developing world largesse as deals sour

- CHINA LOANS: Old flame

- 9 August 2016 CCTV Interview at Maritime Silk Road Conference

- August 2016 – FDI Intelligence Unit of the Financial Times

- 6 July 2016 – AIIB and NDB dominate China’s outbound investment

- 9 May, 2016 – Financial Times – James Kynge How the Silk Road plans will be financed

- May/June 2016 – If you build it, will they come?

- 1 April 2016 – China’s ambitions for Asia show through in ‘Silk Road’ lending

- 20 January 2016 – One Belt One Road sends Chinese outbound lending to 7-year high

PRESS ARTICLES 2015

- 12 December 2015 China to aid indebted African sovereign

- 25 November 2015 China’s New Silk Road Dream

- 22 October 2015 – Chinese investment along One Belt One Road revealed

- 16 October 2015 – Why we should hold out a friendly hand to China

- 10 Sep 2015 – Bangladesh favours Japan for port and power plant, in blow to China

- China Takes Its Debt-Driven Growth Model Overseas, 6 August, 2015

- 1 July 2015 – Massive Chinese lending directed to Silk Road

- 15 June 2015 – Chinese overseas lending dominated by One Belt One Road strategy

- 31 May 2015 – Chinese policy banks perform better since launch of Belt and Road Initiative

- 31 May 2015 – Belt and Road Initiative – Xin Hua

PRESS ARTICLES 2014

- 30 September 2014 – The signs are that Balfour Beatty has not yet reached the bottom – The Independent – Ben Chu

- 26 to 28 September 2014 – Terra Parzival Michaelmas 2014 Council Meeting!

- 28 August 2014 Zhang Chunyan in London and Zheng Yangpeng in Beijing – China Daily Europe

- 16 July 2014 – Nationale Suisse

- 27 February 2014 – Ukraine a setback in China’s eastern Europe strategy – Financial Times – James Kynge

- 20 February 2014 – Could China’s credit hangover prove to be a headache for HSBC? – The Independent – Ben Chu